Early Christian & Byzantine Art

6 min read

Period: c. 200 CE – 1453 CE (Early Christian c. 200-500; Byzantine c. 500-1453) Region: Roman Empire, then Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire centered on Constantinople (Istanbul); Italy (esp. Ravenna), Balkans, Eastern Europe, Near East

Overview & Key Characteristics

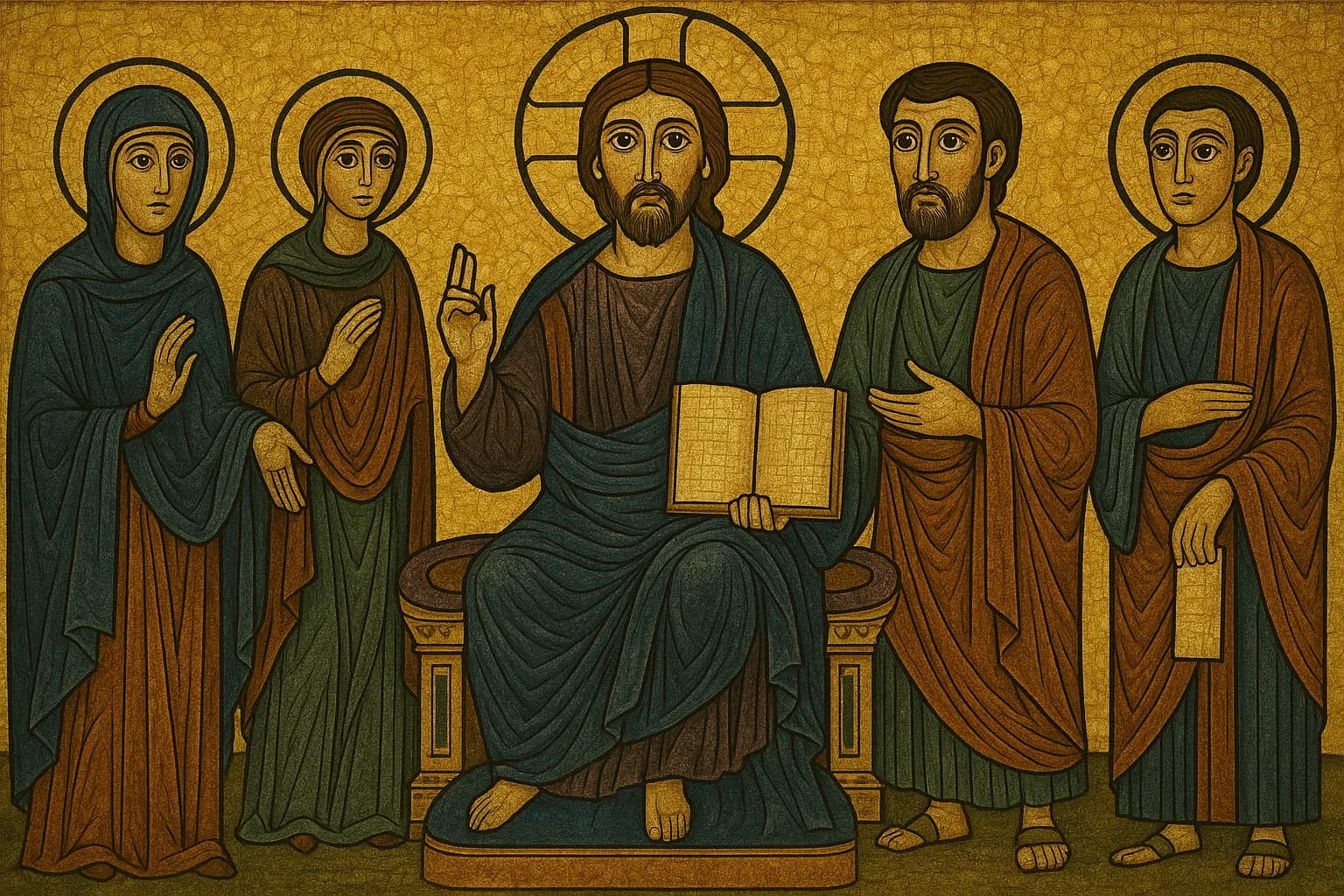

Early Christian art emerged within the Roman Empire (c. 2nd-5th centuries CE), initially adapting existing Roman forms (like the basilica, sarcophagi, and painting styles found in catacombs) to express Christian beliefs, often discreetly before Christianity's legalization. Following the establishment of Constantinople as the capital (330 CE) and the formal division of the Empire, Byzantine art developed as the distinct artistic tradition of the Eastern Roman Empire (c. 5th century - 1453). Deeply intertwined with Orthodox Christian theology and Imperial power, Byzantine art prioritized the spiritual and divine over classical naturalism. It is renowned for its majestic church architecture (often featuring domes), brilliant mosaics that covered interiors, devotional icon paintings, intricate manuscript illuminations, and luxury objects (like ivory carvings). The style generally moved towards flatness, elongation, hieratic formality, and rich symbolism to convey otherworldly realities.

Summary of Common Characteristics (Emphasizing Byzantine, with Early Christian Roots):

| Feature | Characteristic Description |

|---|---|

| Light | Symbolic & Ethereal: Gold backgrounds in mosaics/icons represent divine light (Tabor Light). Architectural design (e.g., Hagia Sophia's dome windows) aimed to dematerialize structure with light. |

| Surface/Texture | Otherworldly Richness: Glistening glass mosaics, polished ivory, gold leaf, luminous pigments in icons and manuscripts. Focus on preciousness over natural texture. |

| Figures | Stylized & Hieratic: Frontal poses, elongated proportions, large eyes, minimal sense of volume. Drapery defined by linear patterns, concealing the body. Hierarchical scale dictates size based on spiritual importance. |

| Space/Depth | Flat & Spiritual: Rejection of classical perspective. Figures often appear to float against undefined, typically gold, backgrounds. Ambiguous spatial relationships emphasize a non-earthly realm. Reverse perspective sometimes used in icons. |

| Color Palette | Rich & Symbolic: Gold (divinity, heaven), Imperial Purple, Deep Blues (truth, transcendence), Reds (humanity, martyrdom, royalty), White (purity, resurrection), Green (life, fertility). Applied in flat, symbolic areas. |

| Composition | Hierarchical & Formal: Central figures (Christ, Virgin Mary) dominate. Often symmetrical, reflecting celestial or imperial order and liturgy. Conveys stability, order, and timelessness. |

| Details/Lines | Strong outlines define forms. Linear conventions for drapery folds. Details emphasize symbolic attributes (halos, books, crosses) rather than naturalistic observation. Intricate decorative patterns are common. |

| Mood/Emotion | Predominantly solemn, spiritual, majestic, transcendent, and didactic. Aims to inspire awe, reverence, and understanding of theological concepts, rather than depicting worldly emotion (though increased expressiveness appears later). |

| Subject Matter | Overwhelmingly Religious: Christ (esp. Pantocrator - Ruler of All, scenes from his life), The Virgin Mary (Theotokos - God-bearer), Saints, Angels, Apostles, Prophets, Biblical narratives (Old & New Testament stories, parables), Church Fathers, Councils, Imperial portraits (emperors/empresses depicted as divinely appointed rulers receiving or offering insignia). |

Key Developments:

- Early Christian Phase (c. 200-500): Adaptation of Roman basilica plan for churches, development of Christian iconography (often using typology), catacomb paintings, carved sarcophagi. Centered largely in Rome and other major Roman cities.

- Byzantine Phase (c. 500-1453): Flourished in Constantinople. Development of the central-plan domed church (Hagia Sophia). Golden age of mosaic decoration (Ravenna, Constantinople). Icon painting becomes central to Orthodox devotion. Interrupted by Iconoclasm (726-843), which led to destruction of figurative art and temporary focus on symbols like the cross. Post-Iconoclasm saw a revival and standardization of iconography (Middle Byzantine), followed by periods of renewed dynamism and emotion (Late Byzantine/Palaeologan Renaissance).

Historical Context & Influences

Key historical events shaped this art:

- Constantine the Great's Edict of Milan (313 CE) legalized Christianity.

- Founding of Constantinople (330 CE) shifted the Empire's center eastward.

- Official division of the Roman Empire (395 CE).

- Fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 CE), leaving Byzantium as the Roman successor state.

- Reign of Justinian I (527-565 CE): Major building projects (Hagia Sophia), codification of law.

- Iconoclastic Controversy (726-843 CE): Debates over the use of religious images.

- The Great Schism (1054 CE) formally separated Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

- Crusades (from 1096 CE): Increased contact and conflict with Western Europe; Sack of Constantinople (1204) weakened the Empire.

- Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks (1453 CE), ending the Byzantine Empire.

Influences: Rooted in Late Roman art. Incorporated stylistic elements from the Near East (Syria, Palestine, Persia - e.g., frontality, decorative patterns). Byzantine art became profoundly influential on: Islamic art and architecture (especially early mosques), Medieval Western European art (Romanesque, Gothic), and formed the direct foundation for the art of Eastern Orthodox nations (Russia, Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania).

Key Artists & Their Contributions

As with much pre-Renaissance art, most artists were anonymous members of workshops, valued for their skill in faithfully reproducing established iconographic types according to Church doctrine.

- Anthemius of Tralles & Isidorus of Miletus (Early Byzantine, 6th c. CE): Not traditional artists, but mathematicians and scientists commissioned by Emperor Justinian I to design Hagia Sophia. Their revolutionary use of geometry and structure (especially the pendentives supporting the massive central dome) created one of history's most awe-inspiring interior spaces.

- Later manuscript illuminators and icon painters (especially during the Palaeologan period and in post-Byzantine centers like Crete) sometimes became known, such as Theophanes the Greek, who worked in both Byzantium and Russia.

Notable Works / Sites

- Early Christian: Catacomb paintings (Rome, Naples), Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (Vatican), Basilica of Santa Sabina (Rome), Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (Ravenna - early mosaics), Old St. Peter's Basilica (Rome - destroyed).

- Early Byzantine (Justinianic Era & before Iconoclasm): Hagia Sophia (Istanbul), Church of San Vitale (Ravenna - famous mosaics of Justinian and Theodora), Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (Ravenna - procession mosaics), Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe (Ravenna), Icons from St. Catherine's Monastery (Mount Sinai, Egypt), illuminated manuscripts like the Vienna Genesis and Rabbula Gospels.

- Middle Byzantine (Post-Iconoclasm): Mosaics at Hosios Loukas Monastery and Daphni Monastery (Greece), St. Mark's Basilica (Venice - Byzantine artisans/influence), illuminated manuscripts like the Paris Psalter, ivory carvings like the Harbaville Triptych.

- Late Byzantine (Palaeologan Renaissance): Mosaics and frescoes of the Chora Church (Kariye Museum) (Istanbul), frescoes in the churches of Mystras (Greece), development of major icon painting schools (leading to masters like Andrei Rublev in Russia, influenced by Byzantium).

Legacy and Influence

Early Christian and Byzantine art played a crucial role in shaping European and Near Eastern visual culture:

- It established the core iconography of Christianity that persisted for centuries.

- Developed enduring church architectural forms (domed central plan, Greek cross).

- Mastered the art of large-scale mosaic decoration and refined icon painting techniques.

- Preserved classical texts and knowledge through manuscript copying and illumination.

- Provided the artistic foundation for all Eastern Orthodox cultures.

- Significantly influenced Islamic art (e.g., use of mosaics, dome structures) and Western Medieval art (iconography, compositional strategies). Its spiritual focus and stylized forms offered an alternative to classical naturalism that resonated throughout the Middle Ages.