Echoneo-25-0: Conceptual Art Concept depicted in Prehistoric Style

6 min read

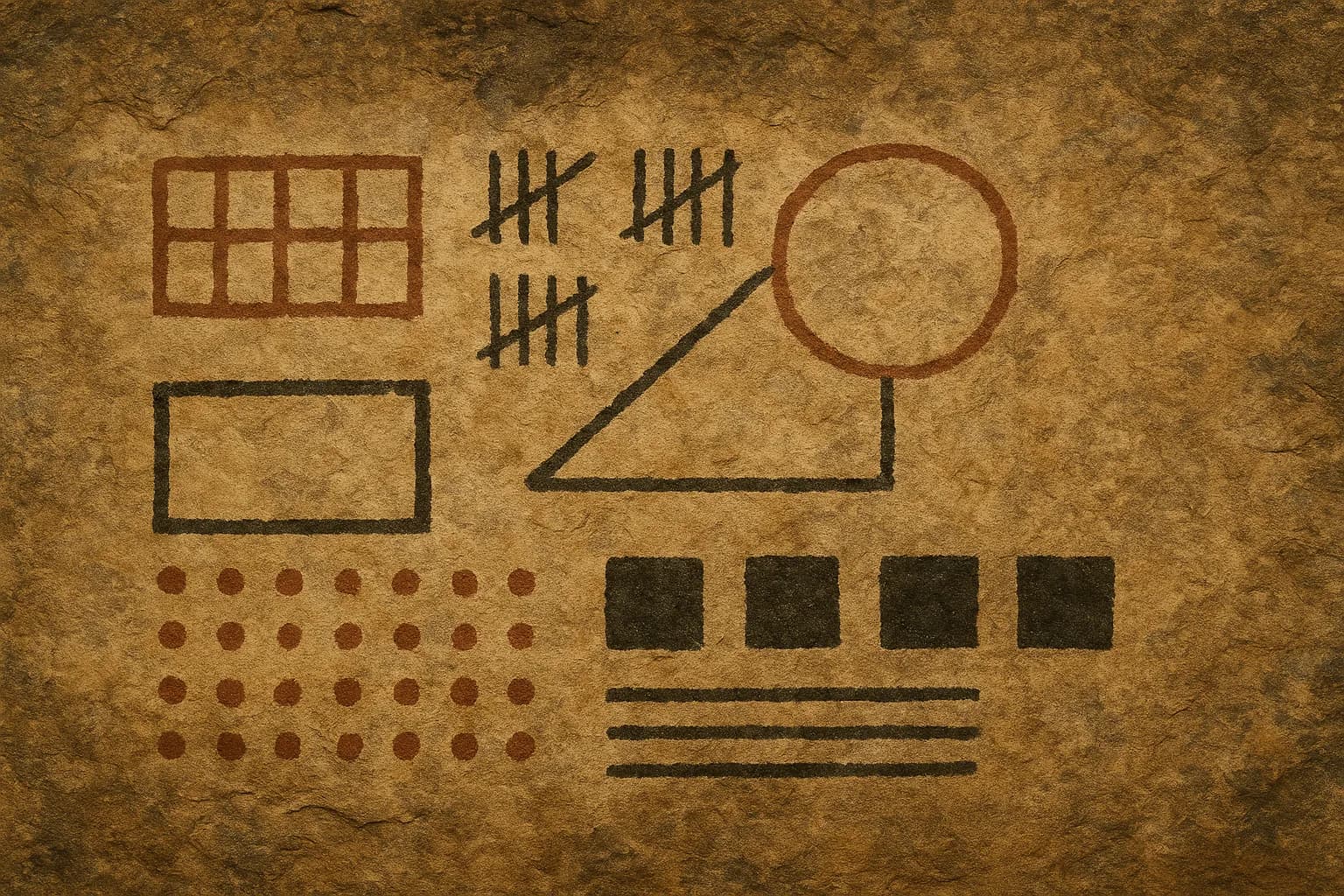

Artwork [25,0] presents the fusion of the Conceptual Art concept with the Prehistoric style.

As the architect of the Echoneo project and a dedicated art historian, I find immense fascination in the digital collision of disparate art historical epochs. Our [25,0] coordinate piece offers a profound inquiry into the very essence of artistic creation and perception. Let us delve into its foundational layers.

The Concept: Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art, flourishing primarily between 1965 and 1975, fundamentally recalibrated the parameters of artistic discourse. Its radical premise asserted the preeminence of the idea or concept over the aesthetic object itself, deeming the physical manifestation merely a vestige or documentation of the originating thought. Joseph Kosuth's seminal "One and Three Chairs" exemplifies this stance, presenting an actual chair, its photographic representation, and its dictionary definition as equal, interlocking components of a singular artistic statement.

Its core themes revolved around an exhaustive interrogation of art's definition and its inherent boundaries. This intellectual movement sought to dematerialize the artwork, shifting focus from tangible form to pure cerebration, thereby challenging established notions of artistic value and production. Key subjects often included linguistic analysis, semiotics, the critique of art institutions, and the very mechanisms of meaning-making. The narrative was inherently analytical and self-referential, compelling viewers to engage in rigorous intellectual questioning rather than passive visual consumption. Emotional resonance, when it occurred, stemmed not from direct aesthetic pleasure but from the cognitive friction generated by profound philosophical inquiry into art’s very being.

The Style: Prehistoric Art

Dating back approximately 40,000 to 3,000 BCE, Prehistoric Art, epitomized by the magnificent Lascaux cave paintings, represents humanity's earliest visual expressions. This primal aesthetic employed a direct, intuitive visual language. Its visuals are characterized by robust contour lines, abstract or schematic human figures often rendered as stick-like forms, and potent symbolic animal representations. The artistry prioritizes vitality and movement over anatomical precision, frequently depicting creatures in profile with an astonishing sense of presence.

Techniques were rudimentary yet remarkably effective: pigments derived from natural earth—ochres, charcoals, manganese—were applied through dabbing, blowing, or direct finger painting. Engraving lines into the rock surface further defined forms, harnessing the very texture of the cave wall as an integral part of the composition. The color palette was inherently restricted, dominated by earthy reds, blacks, and yellows. The rough, uneven rock surfaces introduced an organic texture, deeply integrating the artwork with its ancient canvas. Compositionally, figures appear scattered, isolated, or in loose, seemingly unarranged clusters, devoid of formal ground lines or discernible perspective. This reflected an opportunistic and timeless approach, where figures floated within an indeterminate space. The specialty of this art lies in its raw, unfiltered honesty, its profound connection to the environment, and its ability to communicate across millennia without reliance on complex visual syntax.

The Prompt's Intent for [Conceptual Art Concept, Prehistoric Style]

The specific creative challenge posed to the AI was to forge a dialogue between two radically different modes of artistic expression: the highly intellectual, dematerialized philosophy of Conceptual Art and the primal, visually grounded aesthetic of Prehistoric Art. The core instruction was to render the essence of a conceptual artwork—an idea or definition—through the visual vocabulary of Upper Paleolithic cave painting.

This required the AI to interpret abstract notions like "primacy of idea" or "language as art" using simplified forms, strong contours, and the limited palette inherent to ancient wall paintings. It was tasked with depicting, for instance, a concept akin to Kosuth's "One and Three Chairs" (an actual object, its image, its definition) not with photographs and text, but with the rough, organic immediacy of a cave drawing. The instructions emphasized simulating the textured rock surface, employing spontaneous pigment application techniques, and adhering to flat, indeterminate lighting. The underlying goal was to provoke intellectual engagement within a visually ancient framework, forcing a contemplation of what constitutes "art" when stripped of all modern context and reduced to its most elemental visual form.

Observations on the Result

The AI's interpretation of this extraordinary directive yields a fascinating, indeed jarring, visual outcome. We observe a scene rendered with the stark, unadorned aesthetic of a cave painting. Schematic figures, perhaps representing chairs or rudimentary objects, are etched or painted onto a simulated rough rock surface with an immediate, almost spontaneous application. What is truly striking is how the AI attempts to materialize the idea of a definition or a concept within this primal visual language. Instead of literal text, we might discern sequences of abstract symbols, primal glyphs, or simplified pictograms intended to convey linguistic meaning.

The success lies in the stark, almost audacious contrast it establishes. The sophisticated, self-referential critique of Conceptual Art finds itself stripped bare, translated into the elemental language of our earliest ancestors. The simulation of uneven rock and earth pigments grounds the ethereal concept in a visceral materiality, creating an unexpected permanence for an art form dedicated to dematerialization. The surprising element is the efficacy of this reduction; the core conceptual tension—the interplay between object, image, and definition—is still discernible, albeit radically re-coded. However, dissonance arises from the inherent tension between the intellectual detachment sought by Conceptual Art and the raw, ritualistic immediacy of the Prehistoric style, inviting a deeper ponderance on the nature of understanding itself.

Significance of [Conceptual Art Concept, Prehistoric Style]

The fusion of Conceptual Art's intellectual rigor with Prehistoric Art's primal immediacy reveals profound insights into the underlying assumptions and latent potentials within both movements. Conceptual Art, often perceived as a late modernist phenomenon rooted in post-linguistic philosophy, is suddenly stripped of its institutional trappings and presented in a context where language itself is in its nascent, symbolic form. This collision exposes the inherent human drive to categorize, define, and represent, regardless of historical period or technological advancement.

One profound irony lies in the 'dematerialization' central to Conceptual Art being rendered in the most enduring and elemental material: rock. This forces us to question whether the idea truly transcends its physical support, or if even the most abstract concept requires some form of tangible anchoring to exist in human consciousness. Conversely, it imbues Prehistoric Art with a new layer of conceptual depth, prompting us to consider if those early marks were merely representations, or if they too, contained profound, abstract ideas about existence, being, and the definition of their world. Perhaps the earliest handprint was not just a signature, but a conceptual assertion of self-presence.

This hybrid work highlights the universal human compulsion to interpret and make meaning. It suggests that the quest for definition, as explored by Kosuth, is not a modern intellectual construct but a timeless, fundamental human endeavor, echoed in the very first symbolic marks on a cave wall. The beauty lies in this profound reduction, demonstrating that even the most complex philosophical questions can be distilled to their most primal essence, thereby offering a fresh perspective on the continuous, evolving dialogue of art throughout human history.

The Prompt behind the the Artwork [25,0] "Conceptual Art Concept depicted in Prehistoric Style":

Concept:Present the artwork primarily as an idea, which might be communicated through text, instructions, photographs, maps, or documentation rather than a traditional aesthetic object. For example, visualize Joseph Kosuth's "One and Three Chairs" (an actual chair, a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition of "chair"). The focus is on the thought process, definition, or concept itself, often questioning the nature of art and its institutions.Emotion target:Prioritize intellectual engagement, questioning, and critical thinking over direct emotional response. Aim to provoke thought about the definition of art, language, meaning, and context. Any emotional impact often arises from contemplating the idea presented or the critique implied, rather than from the visual form itself.Art Style:Use a Prehistoric Art approach based on Upper Paleolithic cave paintings. Focus on simplified, primal visual language characterized by strong contour lines, abstract human figures (schematic or stick-like), and symbolic representations. Emphasize rough, spontaneous application techniques such as dabbing, blowing pigments, and engraving lines into a textured rock surface. Natural earth pigments — ochres, charcoals, and manganese — dominate the limited color palette. Integrate the irregularities and textures of the rock wall into the composition to achieve an organic, raw aesthetic.Scene & Technical Details:Render the scene in a 4:3 aspect ratio (1536×1024 resolution). Use flat, indeterminate lighting without a discernible source to maintain the prehistoric cave environment feeling. Employ a direct, frontal or slight profile view, preserving the visual flatness typical of cave art. Simulate the rough, uneven rock surface texture as the canvas, allowing it to interact naturally with the figures. Avoid realistic anatomy, perspective, smooth surfaces, complex shading, or detailed architectural elements. Figures should appear scattered, isolated, or loosely clustered without formal composition or ground lines, reflecting the opportunistic, timeless nature of prehistoric wall art.